Drilling Longer Laterals

What it means for the industry and the environment.

February 2, 2022

Recently CNX Resources and drilling partner Schlumberger Limited (NYSE: SLB) set company records for natural gas lateral length, with three successive laterals exceeding 21,836 ft. The last and longest one reached 22,565 ft. A decade ago, the average CNX lateral was roughly 5,000 ft. That's a 450% increase in just 10 years.

Longer laterals here in Appalachia have already impacted the energy landscape internationally, and they continue to do so. But they require a confluence of technology, planning, and infrastructure to accomplish.

What Makes a Lateral?

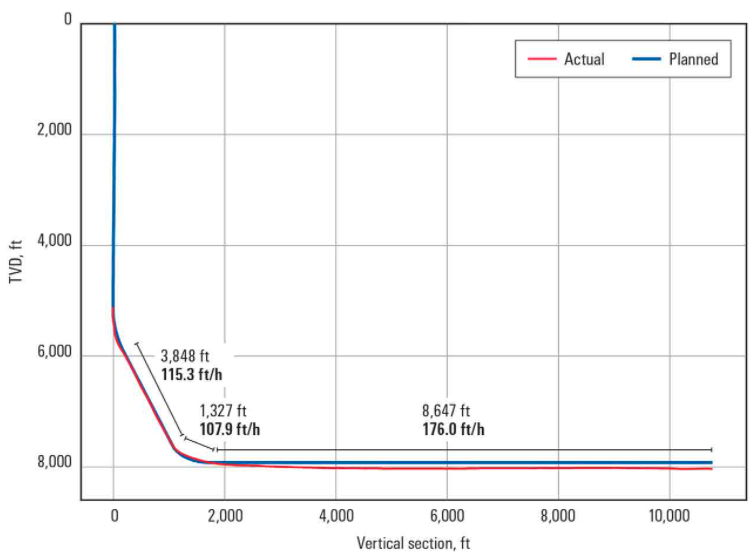

A "lateral" is the term used to describe a natural gas well that was drilled laterally in addition to vertically. Sometimes referred to as "horizontal drilling," the process of drilling a lateral begins vertically, with the drill bit descending several thousand feet to reach the layer of Marcellus or Utica shale where deposits of natural gas reside. As it approaches the shale, the bit begins to curve over the course of a few hundred feet until it is parallel with the layer of shale.

Just like the surface terrain, the layer of shale may rise and fall as it progresses laterally. The drill bit follows these subsurface inclination changes so that natural gas can be harvested along the full length of the lateral. The ability to pilot a drill up, down, left and right is referred to as "directional drilling," and its deployment in Appalachia has made Pennsylvania the second largest natural gas producer in the country.

Directional Drilling in Appalachia

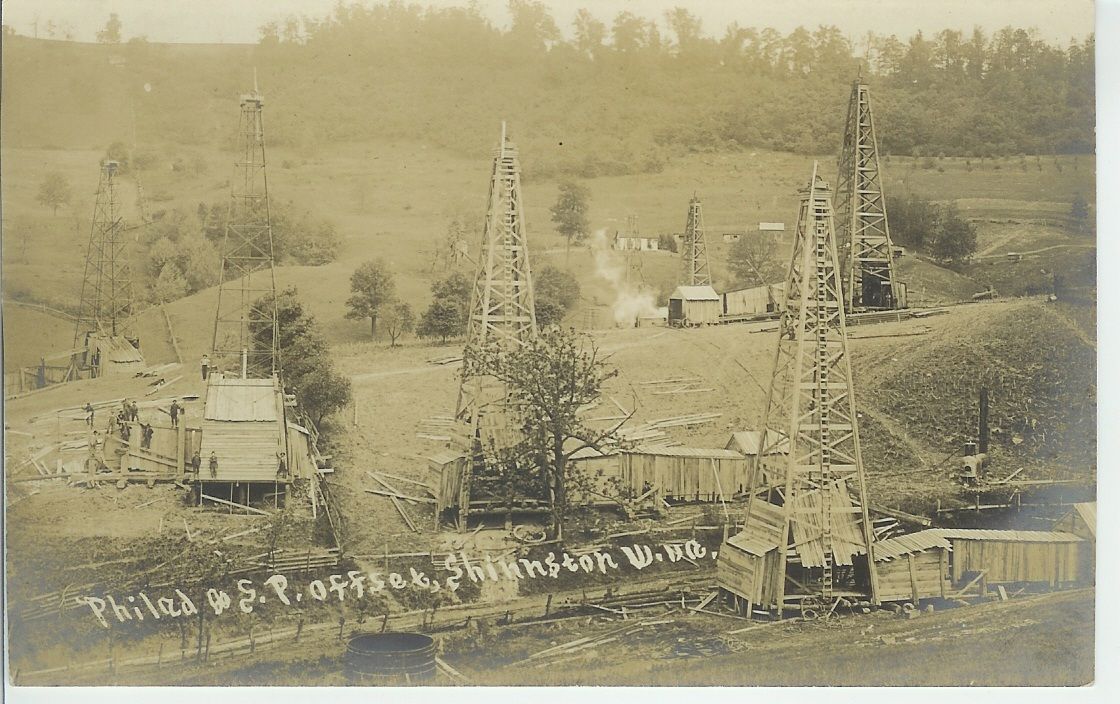

The Appalachian basin has a long history of drilling with vertical wells dating back to the 1850's and the discovery of oil in Titusville, PA. However, these early vertical wells were ineffective for producing gas due to the small subsurface acreage they could access.

"Slant drilling" was introduced in the 1930's offering greater subsurface access. It would become widely used around the world, but it was still limited in Appalachian due to the mountainous terrain and the depth of the gas deposits.

It wasn't until the 1990's that directional drilling as we know it, with vertical, curve and lateral sections, was pioneered. When it was applied to Marcellus Shale in Appalachia soon after, directional drilling here would take on an identity of its own.

In the mid 2000's, directional drilling was borrowed from other (predominantly flatter) parts of the world and use to access Appalachian basin gas. However, the earliest laterals here would barely exceed 1,000 feet. The technology had to evolve in order to accommodate the doglegs of Marcellus and Utica shale. Less than two decades later, laterals are exceeding 22,000 ft with regularity. Efficiencies in natural gas production have improved over 1,000% largely due to refinements in directional drilling here in Appalachia.

Advancing Technology

Early directional drilling required using many different techniques to drill the various parts of the well. Rotational methods, sliding methods, a wide variety of drill bits, and frequent repositioning of the drillstring to change the direction of the wellpath were all critical.

Over time, technology advanced such that drillers like Schlumberger can drill both curved and straight sections of the well with one steerable rotary tool. A flexible internal fulcrum can "point" the tool/drill bit in a desired direction. While multiple tools are still required for the top part of the well, the great majority of a lateral is now achieved with a single tool.

3D seismic imaging allows geologists to map the path of a lateral over several miles. Once the drill is underground, dual-telemetry has improved communication with the tool so the pilot knows its precise position from the surface.

The goal is to plan and execute a wellbore that is as smooth as possible. This decreases torque and drag. Variances need to be minimized because it's not just the drill bit that needs to pass through. The entire well is lined with steel casing before the well begins to produce gas.

What it Means

Drilling longer laterals has enabled drastic reductions in surface disturbance while producing immense amounts of energy. For example, a modern horizontal well can produce the same amount of natural gas as roughly 30 vertical wells all from a single point on the surface.

Modern directional drilling also enables multiple wells on the same well pad. In 2012, the average CNX well pad had 5 wells with an average lateral length of 4,825 ft. In 2021, the average CNX well pad had 14 wells with an average length of 12,686 ft and a long of 22,565 ft. A modern CNX well pad accesses roughly 3,200 subsurface acres compared to 500 acres in 2012. That's a 640% increase in acreage efficiency in ten years. That also means 5 well pads can be eliminated.

The implications go beyond those numbers. Fewer wells means reductions in truck traffic, construction, emissions, operational costs and reducing the surrounding infrastructure required to produce and transport the gas. Longer laterals also means improving financial rates of return, improving safety and increasing the amount of energy that can be harvested as well as the speed.

Looking to the Future

Can efficiency gains of 640% continue into the future? The answer has a lot to do with factors other than technology. Drilling a lateral requires the acquisition of drilling rights from landowners, permitting with local and federal authorities, pipelines to transport increasingly larger amount of gas, and all the associated coordination. As the stakes increase, so do the hurdles and the planning required.

Most natural gas wells take 2-3 years to plan. Engineers must forecast based on the technology they anticipate being available once all the administrative elements have been addressed.

The efficiency gains in natural gas may maintain the leaps and bounds of the last 15 years, but they will continue to grow. Engineers at CNX are already forecasting for it.